It doesn’t take long to make David Hockney laugh.

At nearly 88 years old, he is frail but still very dapper in his beige, red and black houndstooth suit with a white silk handkerchief poking out of the pocket, and trademark round yellow glasses perched on his nose.

Britain’s most popular artist chuckles a lot, his throaty laugh betraying his many years of smoking.

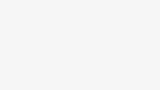

But, he tells me, as a young student from Bradford at the Royal College of Art in London in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the other students laughed at him.

Geoffrey Reeve/Bridgeman Art Library

Geoffrey Reeve/Bridgeman Art Library“People would mock my accent,” he says. But it didn’t faze him. Hockney knew his worth even then. “I’d look at their artworks and I’d think, well, if I drew like that, I’d keep my mouth shut.”

What would the young boy growing up in Bradford think about the life he’d go on to have and the work he’d create?

“He’d have thought it was pretty daft.”

For decades, Hockney has been among the world’s greatest living artists, and he is now opening his biggest ever show.

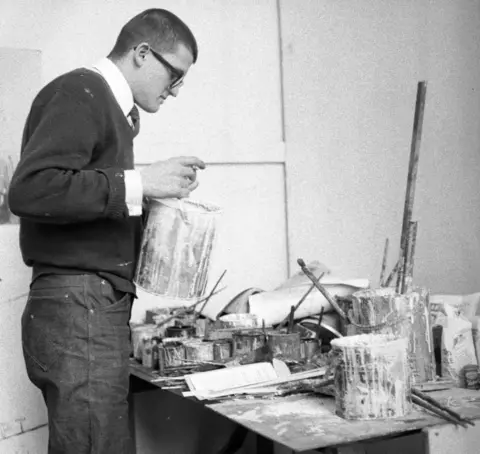

David Hockney/Prudence Cuming Associates/Tate

David Hockney/Prudence Cuming Associates/TateAs we sit together in a vast gallery at the Louis Vuitton Foundation, a stunning museum designed in reflective glass on the edge of the Bois de Boulogne in Paris, I ask him what he thinks of the exhibition.

He says it’s his best ever, and bursts into laughter again.

It’s an expression of pure delight at the 11 rooms filled across four floors with his art – and at being alive to see it. “I’m just laughing, I mean we made it!”

Two years ago, when they started planning the exhibition, “I just thought I probably wouldn’t be here”, he says. “I’m still a smoker, a happy smoker fed up of bossy people telling you what to do… but I didn’t know.”

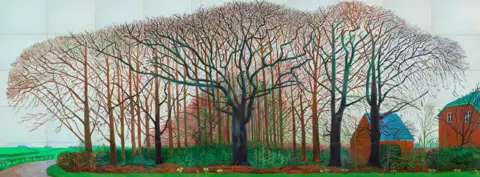

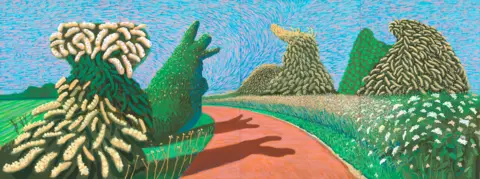

Hockney is sporting a badge that says “End Bossiness Now” in a gallery dedicated to his love of spring. During the pandemic in 2020, Hockney, who was living in Normandy, used his iPad to paint the trees and flowers blooming as spring arrived.

Those 220 iPad works adorn this gallery, floor to ceiling, the walls bursting with blossom and pure joy, made at a time when the world wasn’t feeling very hopeful.

Visitors to the show are greeted at the entrance by Hockney’s message from that time: “Do remember they can’t cancel the spring.”

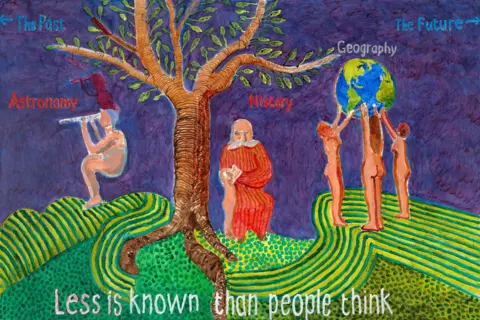

David Hockney

David HockneyHockney has been in poor health. He now has two full-time carers, who have accompanied him to Paris from London, where he now lives. Portraits of both, sitting in their dark blue nurses’ uniforms, are the most recent works in the exhibition, made earlier this year.

A self-portrait of Hockney, painting and smoking a cigarette (his two great loves) is also very new.

David Hockney/Jonathan Wilkinson

David Hockney/Jonathan WilkinsonHe still paints for four to six hours every day, he tells me.

He believes you can’t judge a painter until their last work is done – but looking at his own work gathered together in Paris, “I can see what I was always trying to do, really”.

And he promises that “anybody who has just a little visual sensibility will really enjoy this show”.

His great-nephew Richard Hockney, who has regularly sat for him for 28 years, since he was four years old, including for this exhibition, tells me everyone was determined the artist would make it to Paris.

The night before, Hockney got into a car with his dachshund Tess to be driven across the Channel. And on the morning before they left, they were playing him variations of the jazz classic April in Paris.

Having arrived, “he is glowing”, Richard says. “I think this will keep him going for a long, long time, to be honest.”

And with spring unfolding in the French capital, it’s entirely appropriate that the artist known for chronicling spring would open his exhibition, David Hockney 25, now.

This is a man who would fly back from his home in Los Angeles when he heard the hawthorn had begun to blossom in his native Yorkshire, just so he could paint the dazzling spectacle.

Some of his earliest works, including probably his most famous, A Bigger Splash, are also on show in Paris.

That painting, capturing the moment of a swimmer diving into a Santa Monica pool, is on the wall next to Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures), the south of France pool painting that broke records when it sold at auction in 2018 for £70m.

David Hockney/Tate

David Hockney/Tate David Hockney/Art Gallery of New South Wales/Jenni Carter

David Hockney/Art Gallery of New South Wales/Jenni CarterNext to those are Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, another of Hockney’s most recognisable works, which depicts his good friend Celia Birtwell and her husband Ossie Clark, with their white cat on his knee. Seeing them brought together in one room is spectacular.

But the show’s main focus is the last 25 years because “it’s 2025”, he says. “People think it’s miserable, but in 1925 they’d had the First World War.”

It’s a visual feast, full of the bright colours and optimism for which Hockney has become known.

“I’ve always had it. I’ve always thought it was an absurd world.”

A world to laugh at, to look at closely, as Hockney does, and to paint vibrantly.

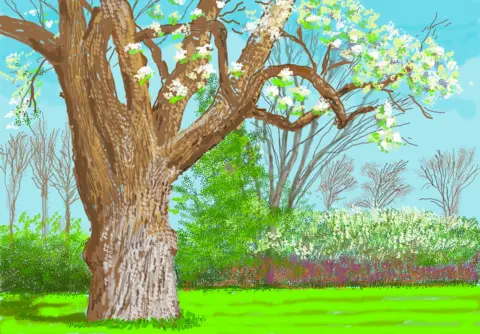

David Hockney/Jonathan Wilkinson

David Hockney/Jonathan WilkinsonSome of the iPad paintings are huge. He’s “amazed they could be blown up so big” when they were created on something so small.

One room is almost pitch dark to show off paintings he did of the Moon, made possible by advances in iPad technology.

There’s also a floor devoted to his portraits (about 60), including a 2022 painting of singer Harry Styles in a striped cardigan with a set of pearls around his neck.

But the rest are the friends and family Hockney knows well – Birtwell, her children and grandchildren, the show’s curator Sir Norman Rosenthal wearing full regalia, Hockney’s partner JP, sometimes with Tess the dog – and two of Richard.

Even though they’re related, when he’s having a portrait done “it’s very surreal looking at him and then realising you’re being painted by David Hockney”, he tells me. “You know he’s always going to create a masterpiece.”

His great uncle chooses to paint people he loves because “he sees the truer representation of yourself than you do”. In one of the portraits, Richard is grinning, in a green and white striped T-shirt.

Because Hockney likes Richard’s cheeky grin, “he will sit there and grin at me because he knows it’s going to make me grin… after six hours, it aches a bit”.

David Hockney/Jonathan Wilkinson

David Hockney/Jonathan Wilkinson David Hockney/Richard Schmidt

David Hockney/Richard SchmidtKing Charles went to visit Hockney at home in London before he travelled. “He’s a very nice man, thoughtful, I thought,” the artist says. “He does watercolours himself.”

But he doesn’t fancy painting the King. “The problem there is the majesty, isn’t it really? I would find that a bit difficult, I think.”

He does, though, have a work on the go, a new painting of his great-nephew.

Richard tells me Hockney “says he’s still got a lot of work to do, which is good”, adding: “As long as that’s in his head, then he’ll keep going.”

The artist says he’ll finish his painting of his great nephew and then “I will paint somebody else. And I just carry on.”

David Hockney 25 is at the Fondation Louis Vuitton, Paris, from 9 April until 31 August.